The Medicaid battle has come and gone again. Senators Graham and Cassidy came up with another plan to attack the Affordable Care Act. Due to the arcane rules of the Senate, they had until the end of September to pass their amendment with only 51 votes (including a tie-breaker from the Vice President); otherwise, they’ll need 60 again. Again, while this was an attack on millions of Americans, disabled and non-, the disability community in particular needed to come together to resist, because if this bill had succeeded, some disabled people who depend on Medicaid would have lost their freedom and others would have lost their lives. The direct action group ADAPT, which arises from the independent living movement, the most visible strand of the disability rights movement, was among the most visible to respond and played a key role in the failure of the Graham-Cassidy amendment.

This is a wonderful thing, but it also discourages some members of our community from participating in political action. To many people, ADAPT has become synonymous with the disability rights movement.

This summer, ADAPTers were at the forefront of the first Medicaid battle. We saw photos of Stephanie Woodward’s hands cuffed at the back of her pink wheelchair and of “Spitfire” Sabel being lifted out of her powerchair and carried off by police. We read the news stories about Denver activists waiting for 59 hours in Senator Gardner’s office for him to meet and eventually being hauled out by police when the he refused. We watched the videos of a Columbus, Ohio, police officer casually walking up behind an activist named Alisa and tipping her wheelchair, dumping her onto the floor, and of Bruce Darling after the action, describing activists getting dragged off to jail without their wheelchairs. We followed along as Anita Cameron and Josue Rodriguez documented vigil in Rochester and El Paso. We watched videos by Jill Jacobs and German Parodi outside the Senate Office Buildings as the final “skinny repeal” vote loomed, and when it was all over, when Senator McCain finally stood with Senators Collins and Murkowski, we recognized ADAPT’s leadership and the vital role that their direct action played in protecting the lives and freedom of those who depend on Medicaid and that it plays in disability rights in general.

Our neighbors watched, too. Nondisabled people were introduced to ADAPT on TV, in magazines and in newspapers. Late one surreal night in a Greyhound station I found myself explaining ADAPT history to total strangers who had never realized that someone like me can ride over-the-road buses. “You know those wheelchair protesters you see on the news?” I asked. All around me, heads nodded. “They’re not new. They’ve been out there for years, fighting for our rights. They’re why I can ride tonight. See, in Denver in the 1970’s….”

We are just ordinary people who joined the movement to fight for our civil rights, our human rights, our right to live and exist and have liberty and life just like everyone else.

– Anita Cameron, National ADAPT

While I was in elementary school, ADAPT members lay down in the streets to bring us lifts on buses. It was their first campaign. While I was institutionalized, ADAPTers were in the streets and crawling up the steps of the US Capitol fighting for the Americans with Disabilities Act, Today they are on the streets and in their legislators’ offices today fighting for the Disability Integration Act. And ADAPTers follow in the tradition of the 504 protesters, who in 1977 took and held a federal building for 25 days in an attempt to get regulations issued so that the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 could be implemented.

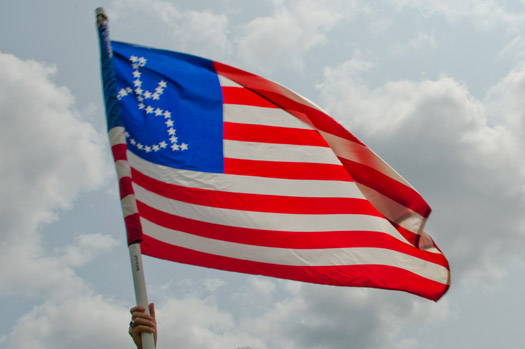

Watching ADAPT members at a national action is stirring. Their flag – an American flag with the international symbol for access replacing the field of stars – soars above them as they march in single file. Watching them break and swarm their targets, chanting, is powerful. Clicking through the selfies at the White House fence, seeing the photographs of individual activists being led or pushed or dragged or carried away from the group by police to arrest, and looking at the images of exhausted activists being released from police custody to cheers is an emotional experience for me. It always has been. It always will be. These are people I hold in the highest esteem and the work they do is important to me. I am proud to have been in DC with them on this last action.

But ADAPT is not the entire disability rights movement, and we must not think that they are.

Many people with disabilities do not know how to get involved in the disability rights field. Many are not educated about their rights or may have not felt comfortable in a disability protest environment. However, the more accessible the disability rights field is to everyone living with a disability, the more powerful the disability rights movement will become, and the harder it will become to ignore disability rights issues in policies. A large unified disability rights community with a single message becomes a force to be reckoned with, more so than individual groups.

– Ryan McGraw, Chicago ADAPT

ADAPT is one piece – a highly visible, powerful, and crucial piece, but one piece among many – of the disability rights movement. It is vital today that we understand that. Today there are powerful Deaf and blind communities. There are the vibrant cross-disability traditions of self-advocacy and independent living. The still-young, neurodiversity movement is coming into its own and demanding a real place at the table – and, for some, a real place out of the streets.

In these difficult days, it is urgent that we shape the disability rights movement to respond with increasing effectiveness to both the need to advance our cause with the government and the need to resist efforts to roll back what has already been won. We need to develop the activists we have and we need to recruit, retain, develop and sustain new activists.

I talked to Marilee Adamski-Smith, who heads ADAPT’s media team, not long ago, and we discussed access to protest. I mentioned that for many autistic people, ADAPT is inaccessible. To her credit, she was eager to see how she could change things – until I began to describe some of the barriers. “Noise. Motion. Chaos. Cops.” Suddenly the problem became clear. There are not always arrests, but noise, motion and chaos are central to the ADAPT protest experience. If ADAPT wants us (and it needs to want us), it needs to offer more roles for members and allies who are not physically at the protest than Adamski-Smith’s team can. While the chaos of the street struggle is not the whole of the tactics ADAPT uses, and while I hope that they will continue to expand their range of tactics so as to be both more inclusive and more unsettling to those in power, those traditional protests are a vital piece of the ongoing work and they are never going to be autistic-friendly. Some of us will be able to do them anyway. Many will not. It’s okay to have things whose core features are not accessible to everyone, as long as there are meaningful and respected ways for us all to participate.

I want opportunities to honor ‘activism’ as multifaceted and not monolithic. Doing research on resources, providing food or care to people who need it, and marching in the streets are all forms of activism and equally valid and needed, but I’d wager only the latter is universally thought of as activism. Particularly when the goal is cross-disability solidarity, it is important to remember that not every kind of activism is accessible to everyone, and that by devaluing or excluding certain types of activism, you are devaluing and excluding certain types of people as well.

-Steph Ban

There are other disability constituencies who face barriers to direct action, too. For example, a central piece of ADAPT tactics involves doing things that make police officers angry, and it is unreasonable to expect anyone for whom the sole goal in any contact with the police is physical survival to engage in that kind of action. A terrifyingly high number of disabled people, including many who are neurodivergent fall into that category.

The executive and legislative branches of our federal government are moving against us. They are trying to take away vital supports, cutting enforcement for access, and threatening special education. More than ever we need every single activist we can get. We can no longer afford the idea that some of us have, that to be a disability rights activist you need to be in the streets with or like ADAPT. That idea is costing us people who have something to offer the movement.

I’ve heard it from too many people this year.

“I want to do disability rights, but I just can’t protest like that.”

“I keep trying to help, but they keep saying, ‘But you’re not at the protests.’”

“But if they want to do disability rights, where are they?”

Not being at the protests cannot mean not being in the movement. Not being at the protests while being in the movement means acting in another way.

Doing something is always better than doing nothing.

– Mike Ervin, Chicago ADAPT

The core characteristic of disability rights activism is and always has been the unexpected. When hearing people defined deaf people as incapable of communication and tried to break the community up, Deaf community fought back with a flowering of language and culture. When sighted people defined blind people as beggars and supplicants, they fought back with great dignity. When the “sane” asserted that psychiatric patients needed others to decide what they needed, those patients demanded self-definition and self-determination. When people with intellectual disabilities were told they were unable to think, they built a movement that stresses education, deliberation and authority. When able-bodied people told physically disabled people they were weak, they went out to fight in the streets. When the inclusionists were told their children naturally required segregation, they fought back by ensuring those children were physically present in their communities. Neurodivergent people have been told for long enough that we are disengaged, that we have none of the skills necessary for social endeavors like protest, and that there really is no way to include us until we become typical. We will fight against that by showing our community and the nation what their exclusion of us has cost them.

We who do disability rights need to recognize and honor and develop everyone on our team. We need to connect people with organizations that are doing work that they want to and are suited to doing. We need to continually look to see who is left out and how we can provide them with opportunities to join us. We need to be honest about what we are asking from people and creative about what there is to ask.

We who want to do disability rights need to be prepared to look beyond the pageantry of direct action, if that is not where we can or where we want to contribute. We need to recognize the other work that is being done, in addition to or instead of the work in the streets. Voter registration, research-gathering, information-sharing, endless phone calls and emails and faxes, visits to legislators’ offices, writing, speaking, photography, video work, public education, networking, signal-boosting, fundraising, artistic work, tactics and strategy, training, direct and indirect support to people doing the front-line work, and organization of the kinds of social and recreational opportunities that build a strong community and give its members the strength to keep going while feeling besieged are all vital. As we discipline ourselves to the old and new tools of effective political advocacy, all of it is needed, and all of it counts.

There is a particular kind of courage in the willingness to make one’s small, imperfect offering — saying, in effect, “I don’t have much to give, but I give it gladly as a contribution to the common good.” When we have that kind of courage, we encourage each other. And as more and more people make their small offerings, the cumulative effect can become something big.

– Parker J. Palmer

I recently attended an awards ceremony the Chicago ADAPT chapter put on, celebrating the work that activists had done over the summer to save Medicaid, and I was proud to see them recognize allies in the movement. They celebrated Senator Tammy Duckworth, Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky, Protect Our Care – Illinois, a coalition that had worked to defend the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and Alison Nodvin Barkoff of the Consortium for Citizens with Disabilities. But what really thrilled me was watching the awards given to the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN) and The Arc.

ASAN and The Arc are two of the organizations doing important work on access to protest. The Arc, knowing the importance of personal stories and knowing how many people they represent who cannot directly go to their Senators’ offices to tell their stories themselves, collected Medicaid stories from across the nation, printed them out, and delivered them directly. ASAN has been doing amazing work with creating Toolkits to provide people with the necessary structure for engagement, and has been developing a proxy calling system, so that people who cannot use phones can nonetheless contact their legislators by telephone, using third parties who read their pre-written messages for them. The ASAN staff, working with volunteers and activists, are beginning to open new roads into the political process for those who have been disenfranchised, not just by powerful nondisabled forces, but by our own movement.

We need to unite now in order to not lament later.

– Josue Rodriguez, Desert ADAPT

I asked Julia Bascom, Executive Director of ASAN, what she thinks access to protest is going to look like in the future. “Access to protest is such a tricky thing,” she told me. “There are lots of things we can do to modify and expand how we think about protests, but fundamentally, large groups of people chanting and getting manhandled and arrested is always going to be less accessible for some people compared to others. Sometimes the answer is just: give us something else to do.

“What can folks who aren’t on site be doing? Protests need amplification through media coverage and social media; how does this enable more people to participate? Jail support is a big need; can different folks play a role there? Depending on the action, water or food or childcare might be needed, and so on. So even just looking at traditional roles can open up a lot of possibilities.

“But beyond that, what would a successful protest held solely on social media look like? Can you get the same results? Do you need to get the same results? We have more questions than answers right now. But we’re realizing that the answers to ‘How do we make access to protests possible for more disabled people?’ and ‘How do we include offsite people in protesting?’ have a lot in common.”

These are the questions I want to see asked and answered, and on the foundation of the answers I want to see what we can build: a movement where different people and constituencies work together and celebrate and support one another’s work, where creative new approaches are opening up the political realm to more and more disenfranchised people. ADAPT’s work is beautiful, but it is not enough. It will never be enough. And, as Julia points out when asking these questions, “If one thing is certain, it’s that the next few years are going to give us plenty of time to refine our answers.

There have been several excellent protests held mainly or through entirely social media.

I am thinking of #AutismSpeaks10 and #CripTheVote every week.

And if protests are accessible for us, they may not be for our peers or companions or trusted people. Learnt this in February when there was a #NoTrumpNoTurnbull protest for people in Manus Island [these people are being resettled in the United States now] and Nauru.

There is another issue they have to tackle. That of Discrimination against those with Disabilities within Healthcare itself.

Not everyone with a Disability has easy access to Healthcare period. And the reason is because they may not have the Financial Means or easy access to Transportation or both. Not having this access makes it easy for Healthcare providers to think the person is Non-Compliant when that is not the case.

This has got to change before some of the people get even sicker or die as a result. Some of the people have very complicated Medical Histories that require regular monitoring.

I have a severe traumatic brain injury and was hired by the court.

I was personally hired by the Clerk of Court and didn’t even have to file a full employment application.

I worked about 4 yrs and was fired when I had a seizure.

All attorneys will not fight the court.

The EEOC is in the courthouse itself and politics I’m sure stopped them from helping.

This is a case of great importance to 54 million disabled including veterans, because if the courts themselves won’t protect these laws then there are no laws!

Very true. Recent court ruled Deafblind do not have right to Deafblind interpreter; then ADA attacks, and administration does not support but mocks disabled.

We can work together and include folks. In GA ADAPT we have qualified interpreter ASL or tactile available every meeting, every action. It’s me, a disabled veteran who also fluent sign languages, but Deafblind folks from Chicago and Atlanta have been instrumental in Adapt; we need everyone.

Those of us in ADAPT know well that our direct action civil disobedience protests are not all there is to disability rights. Far from it. And not all of us can be at every action, whether because of finances, health conditions, schedule conflicts, work, school, or the randomness of typical life occurrences. When Bob and I are absent from actions due to health, deaths in the family, etc., we can usually support from afar with emails, calls, faxes, tweets to or about targets, and/or urge others similarly at home or work to do the same. The social media aspects of ADAPT’s work have become increasingly important and visible, and we definitely need more people who can engage in social media during actions to amplify the message. We can also contact our local media urging coverage of disability rights. Participation is greatly needed by people who can write letters, engage locally with committees, task forces, state legislators and others in power. And getting people to register to vote, and then out to vote is hugely important. There are so many ways to be an advocate and an activist in the disability rights movement…..and ALL ways are both needed and equally important. Those in power need to hear from those in the streets, those in suits and office suites, and most importantly from the public they are paid to serve. Sometimes we can share or ask for ideas of alternative ways to protest/participate, and sometimes creative people show us fantastic new strategies that we haven’t yet thought of- strategies that successfully diversify our approach, and that establish ways for even more people to meaningfully participate. The bottom line is that we are ALL needed, ALL important, contributing in whatever ways we are comfortable and able. #WeAreOne

Wouldn’t my issue of being fired from the court itself be a case of great importance to all,and a statement for millions.

Hey. My name is Brandon, I have a disability. It is because of a car accident that I was a part of 10 years ago. All the stuff you said in this speech, or paragraph’s, or blog post, whatever you might call it, it FINE and GREAT for those of us who can read at a normal speed. But I hate to say that SOME of us CANNOT read at are OLD normal speed. It is MUCH harder for us now that we have this BRAIN INJURY.

I guess I’m telling you this, because I want THIS place to form around ALL disability’s. You know what I’m saying? I would like for ANYBODY to come to your site and be able to get as much out of it as ANY body out there.

However, that is CURRENTLY not the case. I spent a really LOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOONG time reading just a few PARAGRAPH’S of what you wrote. It’s really GREAT…and that is why I’m writing this letter to you now!

I honestly believe that you would have a far greater reader base if you read your idea’s OUT LOUD and recorded them down for EVERYONE to HEAR!

That’s just me talking. But I’m one of the people who your TRYING to REACH…and if you don’t get a recording program up, your probably just never going to see me here…ya know?

Give it some thought. If you need some idea’s for your pieces, write to me. I know a WONDERFUL woman who does EXACTLY what it is that you guy’s SHOULD be doing!

Talk to you SOON! I hope…

Hi Brandon!

I would love to have audio and easy read versions of every article. Unfortunately, NOS Magazine is not currently funded so we don’t have the equipment or time to do that. It is in our long-term plans, though. If you know anybody who might want to help make tha happen, we have a Patreon. http://Www.patreon.com/NOSmag