Note: The following piece contains graphic descriptions of police violence.

February 1st is important for two reasons. It’s the first day of Black History Month. Figures like Harriet Tubman, Leroy Moore, Stephen Wiltshire, Vilissa Thompson, Blind Tom Wiggins and Brad Lomax are iconic in the African Diaspora. They are also Deaf, disabled, and/or neurodivergent. Disability is often erased and overlooked when discussing black history. It shouldn’t be.

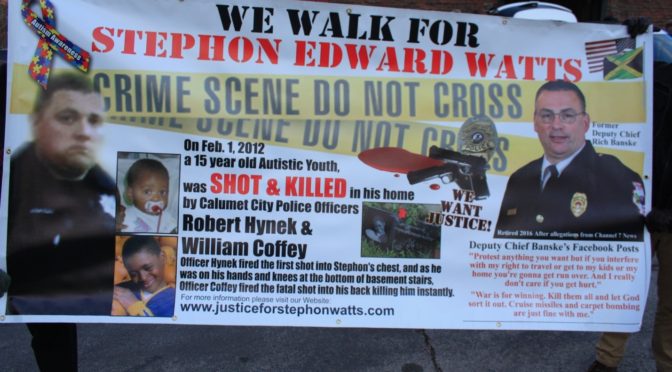

February 1st is also the day that shook Calumet City, IL and the black and disability communities as a whole. This year, February 1st marks the fifth anniversary of Stephon Watts’death. Stephon Watts was a 15-year-old African-American male teen on the autism spectrum. He was interested in computers and aspired to one day become a computer programmer. Five years ago, he was murdered by police.

In 2012, the Calumet City police arrived at Stephon Watts’ home. They were there to “check the house to make sure everyone in the house was safe and not injured,” according to Officer Robert Hyneck‘s summarized interview in the state investigation. officers, including Hynek, charged into the basement where Stephon was located. When Stephon waved a butter knife around, Hynek and another officer, William Coffey, immediately shot him. The second shot killed Stephon instantly.

As an autistic black male, I could have a similar encounter with the police. The police would not face justice for my death. Last year, the Illinois Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the officers Hynek and Coffey. Their actions were ruled justified and “immune from liability for negligence.” Officers Hynek and Coffey had received training on developmental disabilities only once before Stephon’s death. The Calumet City Police still only requires officers to have approximately two hours of training each year on helping people with developmental disabilities who are in crisis. I could die in the hands of the police because my actions could be misunderstood as criminal behavior. The wrong tone of voice, asking questions about why I’m being stopped, or running away because I am afraid of guns could all be death sentences.

In Stephon Watts’ case, the police executed him because his reaction to danger was fatally mistaken for an attempt to stab the police with a butter knife. A butter knife. A butter knife that is used to spread butter or jam on your toast. The worst injury possible is a shallow scratch. There was no need to kill anyone over a butter knife. The police did anyway.

These fears, along with my love for the autism community, drove me to march and speak out during the fifth anniversary of Stephon’s murder. Around 20-30 people joined the Watts’ family in marching two blocks to the Calumet City Police station. Speakers expressing their concerns about why the officers who killed Stephon Watts are still allowed on the streets. They called for training for officers approaching people with disabilities. They demanded governments bring back mental health centers as the first response to crisis instead of police.

I am calling for neurodivergent communities to join the fight for justice.

is important for our community to center. This not an isolated incident. Based on the Ruderman Family Foundation white paper on police violence against people with disabilities, one-third to half of police violence mentioned in the media involves someone in the Deaf or disabled. Some suggest that number could be even higher. Police violence could happen to any one of us. Stephon was one of us, a potential leader gone too soon because of ignorance. We must urge our local communities and governments to protect us from vile actions inflicted by the same people who are supposed to serve and protect us. There need to be more programs by and for us that educate the community and law enforcement on how to approach people with disabilities during a crisis, accurate facts of our respective conditions, and getting to know and accept us.

While it is comforting to unite autistic and neurodivergent people under unified goals and values, we must also recognize that not all of us experience being autistic or otherwise disabled the same way. For people like me and Stephon, our intersected identities can make us targets. It is painful to be reminded that as black people, we are seen as inferior and dangerous. Adding disability to the mix, and you may be even more depressed. People like me and Stephon can feel like outsiders in the black community and outsiders in the neurodiversity community. I believe all multiply marginalized autistic and neurodivergent people must incorporate our various identities into the conversations about the issues we face. We must be more inclusive of people of color, people with non-binary genders, LGBT+ people, people of various faiths, and more.

If we don’t come to together to remember Stephon and fight for justice, then we have failed at achieving justice. We must not fail.

For more information on Stephon Watts and ways you can support the fight for justice, please visit www.justiceforstephonwatts.com.